“What should be, or ought to be, is different from what is” (the error of ‘speculative thinking’ as defined by Robert Thouless).

What can we do to make sure the future we want happens? Is that even possible, when so much is unpredictable and beyond our control – especially if knowing what we “want” isn’t actually that straightforward?

Reality is Contingent

Much of what happens in our careers (and lives) is outside our control – however strong and single-minded our visionary belief. If you ask academics (or anyone) what chance events had a big positive impact on their careers, you always get interesting and surprising stories. Scientific laws define the boundaries of what is possible, but what actually happens is largely down to historical chance happenings: the “contingent” nature of reality as Stephen Jay Gould put it. If you apply for positions, fellowships and so on, the outcome will depend at least on who else happened to apply for the same positions – for example.

Do Something!

Do Something!

Yet it’s also true that you can “make things happen”. This is easy to see if we consider the alternative: if you do nothing at all it’s far less likely that much will happen! You can be confident and make Herculean efforts…that come to nothing; and you can make a tiny nudge that topples an empire. But in both cases you learn a lot along the way and create new possibilities – if you’re not so blinded by self-belief that you are able to see them. “Doing something” has a power – “problems” of any significance require us to start solving them just to understand what the problem actually is.

Capacities for success?

Taken together, those points advocate a strategy for success that is a combination of energy, action, wisdom, playfulness, persistence, courage, and common sense – as you might expect. It doesn’t say “what” to do, but it does indicate why those obvious qualities are, in fact, important.

What to Actually “Do”? (and Why We Don’t).

The common problem is to have a rather fixed view of what we want ‘next’, which at the same time is (perplexingly) rather vague: “some sort of fellowship”; “some sort of intermediate academic position”, or “I don’t really want to think about it”. Which are hard things to execute on.

But, maddeningly, other concrete things do have to be done ‘now’ and within our immediate focus – an experiment; writing a chapter; teaching tomorrow; a meeting…so it’s very difficult to put serious energy into the more vague, further away, futures. The difficulty of a task isn’t so much the technical challenge, it’s more about emotional resistance to doing it, or a lack of clarity about what exactly to actually “do”. We’ll definitely need to master this “managing the present, while creating the future” if we end up responsible for other people.

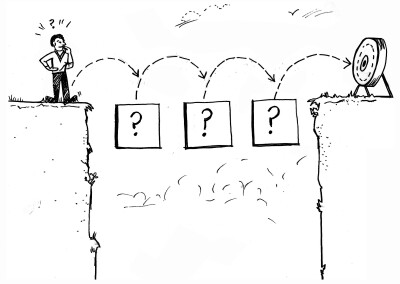

A Trick

The trick is to make the vague definite; the fixed flexible; and the not-doable long term, into short-term things we can easily “do” today. As a caricature, let’s use the ambition of becoming a “Star Researcher” for example. You can find out what you’ll need to have achieved by, say, five years from now. Then you can work backwards to identify steps you can actually execute on today. Time is shorter than we think; but you can achieve more than you imagine you can by making steady small steps of useful progress, from which we will at least learn, and perhaps therefore adapt our plans and goals as we progress. You will end up way ahead of people who never quite got around to it – which may include your ‘old’ self.

The trick is to make the vague definite; the fixed flexible; and the not-doable long term, into short-term things we can easily “do” today. As a caricature, let’s use the ambition of becoming a “Star Researcher” for example. You can find out what you’ll need to have achieved by, say, five years from now. Then you can work backwards to identify steps you can actually execute on today. Time is shorter than we think; but you can achieve more than you imagine you can by making steady small steps of useful progress, from which we will at least learn, and perhaps therefore adapt our plans and goals as we progress. You will end up way ahead of people who never quite got around to it – which may include your ‘old’ self.

One Way to Get Going

Pushing and motivating ourselves can be lonely, hard and delusion prone. Many of us are more effective when working in a team towards a goal we all believe in. For people who enjoy collaboration and find the above relevant to their future, one way is to create a team exercise, where each “topic team” or “research group” is in friendly competition with the other teams, to achieve the most progress for their individual members.

Practise Skills; Build Capacities

Anthropologists tell us that the unique human capacity isn’t intelligence, but imitation. As a species we’re stunningly good at it, unknowingly. Think of language, civilisations, religions, cultures, skills, and professions. It is why humanity has made the unique kind of progress that is has. That being so, you’re perfectly adapted to transcend evolution because you can consciously make choices about what you ‘imitate’, and practise those to acquire abilities and capacities, and hence shape what you become. We’re less ‘fixed’ than we think we are, which is reassuring really.

Adrian West