“To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle requires a creative imagination and marks the real advances in science.” Albert Einstein

We’ve recently designed and facilitated a few workshops which have centred on the need to come up with ideas for a purpose, in teams, in order to move action forward: for a research proposal, to devise business process improvements, and for specific projects.When working together for a purpose we can clearly go about that in different ways. Personalities, experience, timescale and environmental factors all come into play as we wrestle together to create a shape for our ideas and actions that we can all agree on. Sometimes, free-form associative thinking, where we mutually enhance and debate ideas in a fluid conversational way, is just what’s needed, sometimes it’s helpful to have more of a thinking agenda, to scaffold our combined mental efforts.

We made use of a thinking framework in our workshop design to help a variety of people collaborate in a short time, and incorporated techniques to loosen and free up imaginations in order to generate new ideas, within that overall structure.

Above all, for innovation, we can be encouraged by the realisation that it’s not about being a “creative person” – we do not have to have been “born” creative (although some people seem to have a predisposition to think in that way more easily), but we can support our creative thinking with a process and tools which can be formally learnt, and applied in any situation where new ideas are needed.

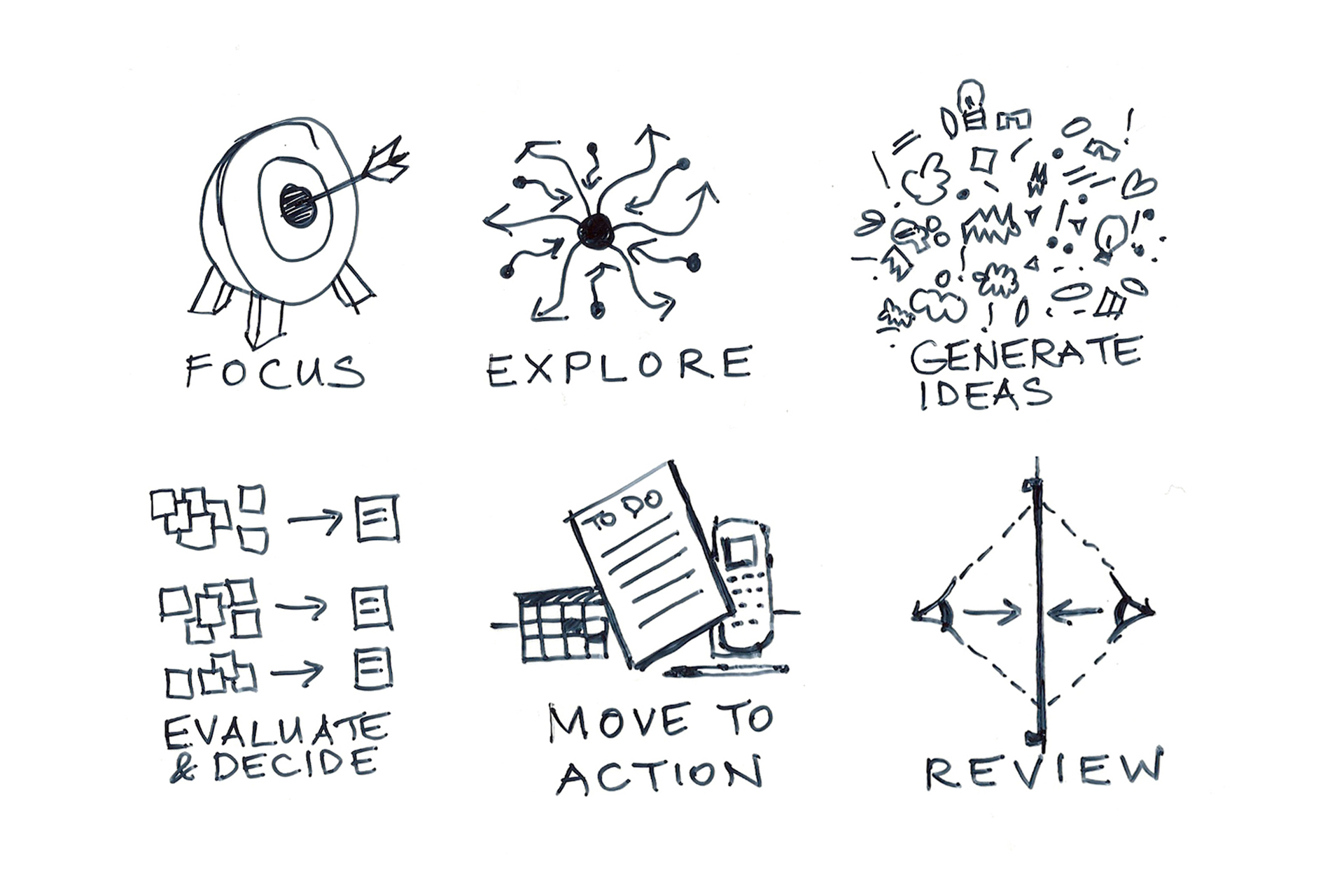

These seem to be the underlying components of an effective creative thinking framework: Following on from my previous post Creative Moves to “Rescue the Princess” I’ll say more about stage 3 “Generate Ideas” using those “Rapunzel” techniques here, and just touch on the other stages briefly.

Following on from my previous post Creative Moves to “Rescue the Princess” I’ll say more about stage 3 “Generate Ideas” using those “Rapunzel” techniques here, and just touch on the other stages briefly.

1. Focus

1. Focus

We first of all consider the focus of our thinking and frame that as a question, having shaped it relentlessly. It is the foundation for the rest of the structure, and having it readily visible helps to remind us of the aim of our thinking, when we go off track.

2. Explore

2. Explore

The important first step for clearer thinking is to see things, without limiting our vision. So we explore the topic in breadth, looking at it from various angles one by one in parallel, and capture our thinking. We can use various questions and methods at this point to ensure we cover the ground effectively – for example the five “Who, Where, What, How, When?” questions.

3. Generate Ideas

3. Generate Ideas

A key skill for creative thinking is to generate ideas as one phase, and concentrate on coming up with as many ideas as we can. We just look for possibilities and options and separate that from any evaluation of them. It is a practice, so the more you do it, the more proficient and skilled you can become at it. Typically, we can start with just what’s on our mind, and move on from there:

a) Immediate “top of the head” ideas – It’s almost impossible to have new ideas unless you empty your mind of all the ideas you already have about “how it should be done” – everything new will just keep coming back to those otherwise. Write down all the “answers” that come to your mind and capture those first. They may end up being your best ideas – why not?

When we are stuck, and we’ve run out of immediate ideas, we can then use deliberate tools to galvanise our thinking. These are about moving us to a new space, where new pathways come to us from there, its not about using understanding, logic or reason to “work out” ideas. We deliberately go to other, sometimes tangential, places in our imagination, and new solutions suggest themselves from those new angles. Examples of some of the “RAPUNZEL” creative thinking techniques in use are outlined below. The real key to using them is familiarity and practice. They are not intellectually challenging, but they are challenging to develop fluency in. If you do though, you will have some deliberate tools which will be effective when you need them.

b) Amplify

For your focus, magnify, exaggerate and caricature any attributes, ideas or solutions upwards, downwards, in scope, or significance, and see where that takes you. Example:

Focus: New ideas for catering

Exaggeration of scope “Just suppose we could have access to any ingredients we wanted at the time we wanted to make the meal”

Ideas: An online ordering service for a mix of ingredients delivered on demand at short notice 24/7, A meal cooked to order delivered as a take-away to a recipe we specified using any ingredients, Social cooking: we phone up all our friends and ask them if they have the ingredients, then invite them round with those to cook a shared meal.

c) Undermine

To escape our habitual mental patterns and look at what we are taking for granted in our thinking. For the focus of your thinking, State any assumptions you are making, Remove those which form the foundation of your thinking (take one at a time), Make different assumptions, and see where this takes you to find new ideas of value.

Example (a real one, from Prudential):

Focus: Ways of increasing sales of life insurance

Assumption: that people have to die before insurance pays out

Removing the assumption: Insurance pays out before we die: “we die before we die”

New idea: Critical illness cover – payout of insurance based on terminal illness

d) Name

For the Focus of your thinking, identify one solution, name what kind of thing that is, generate other solutions of the same kind.

Example:

The Focus: New ideas for business development

One solution: Ask three colleagues what they think the future hot-spots and trends will be and investigate those.

Name the kind of thing this is: Predicting significant developments and working on those (this is one kind of idea, there will be others).

Other solutions: Identify trends in the media; ask 3 people ‘outside’ our business where they see that business market going; find reports on future direction and identify 3 trends; Identify three trends outside of our business field that are likely to impact it and discuss them with colleagues…. (these may, or may not, be ‘good’ ideas, but they are new ideas arising from our initial one, which is what we’re asking for).

e) Locate

For the focus, look for analogous situations, worlds or viewpoints to translate back into the situation, to see it afresh.

Example:

Focus: New ideas for garden design

Analogous viewpoint: An Artist’s world

Ideas: Choose plants and flowers by colour theme to create interesting arrangements for painting, have an area with large slate slabs set in the boundary wall for impromptu chalk drawings, take the work of a famous artist such as Juan Miro, and design the garden layout according to the shapes in his compositions

4. Evaluate and Decide

4. Evaluate and Decide

Having laid out our ideas, we can sort and evaluate them, to select the best to act on. There are various methods that can be applied to help us. These include:

- Grouping similar ideas together.

- Creating a relevant matrix which sorts ideas into different types – for example “Ideas we can use now”, “Great ideas that we want to work on”, “Ideas that suggest other ideas we haven’t explored yet”, “Great ideas that we don’t know how to implement”. You can devise your own.

- We can employ collective intelligence by asking each person in a team to intuitively choose their favourite 3 or so ideas and marking those with, for example, smiley face stickers.

- People can work as a team to agree on the top ideas.

- We can design and use a “Decision Grid” to score ideas with a numbered scale, against relevant pre-determined criteria – for example: judging criteria for a funding proposal or competition, issues such as time, cost, quality.

- All ideas are considered: we would also spend some time “shaping” ideas to really make the most of them. Can the idea be made stronger? How is it different to similar ideas? Can we sharpen it?

5. Move to Action

5. Move to Action

Once we have decided which ideas we want to take forward, we move from the “1% inspiration” to the “99% perspiration” stage. What are we actually going to do, and how are we going to engage in productive activity? For our focus, and the ideas we’ve set our mind on, it helps to picture the outcome we want, and then to really get clear about exactly what the next doable thing or things we can do to move it along, and to continue in that vein.

6. Review

6. Review

The reflection stage of the process is very helpful, if we want to learn from what we do, and one that can be undervalued. We can spend time looking at what was done, the processes involved, the outcomes of our thinking and see what we might do differently or could improve, or reinforce, and incorporate that learning as we go on. Important problems commonly need us to start solving them before we can really understand what the problem actually is: we can’t think things out before hand – just as we can’t know what a new destination is like until we actually get there. For that reason, if we can apply this kind of thinking process in a bigger exploratory context, learning, reviewing and re-learning, we can surely make progress and become more fluent and skilled along the way.

Principles

There are a few key principles underlying all systematic approaches to creativity tools – typically they are approaches to force us out of habitual patterns we lock into. However, many, many books and courses on “creativity” exist, and each has found ways of recasting, re-branding, or trademarking their own approach – an almost infinite variety. This is what can make the topic a confusing one to get into. Although there are key figures in today’s field, (for example Tony Buzan, Edward de Bono, Roger van Oech), there is no one source to go to. Each have their merits, approaches, techniques, emphases and styles. The best advice may be to pick up a few books or scan a few web pages, explore the range and see what you find yourself attracted to. But do also try a few approaches you are not attracted to – after all the idea is to break away from your own habitual ways of approaching and seeing the world!

The value is in taking one or more of these techniques, however they are framed, and really familiarising yourself by trying them out when you need new ideas, or you realise when your thinking is becoming fixed and you’ve lost inspiration. It’s not actually about mental cognition, it’s about perception – seeing differently, which is a “skill”, so you actually have to do it to become fluent. It is more like doing martial arts than intellectual mastery.

In the “Dojo” of your current sphere of influence, what existing moves could you improve or what new moves might you like to make?

Could you frame one of these clearly? Could you try out this framework and a technique or two to come up with ideas and devise actions you could take, that would enrich life?

Sophie Brown

References

One online starting point that describes a range of different tools: http://www.mindtools.com/pages/main/newMN_CT.htm

For a book to refer to, one we recommend is “Serious Creativity: Using the Power of Lateral Thinking to Create New Ideas” – which can be hard to get hold of. It’s by Edward de Bono.