When was the last time you gave some serious thought to the business of making decisions? Rarely? Never? Isn’t it strange, given that making decisions is what we as humans spend most of our time doing, that very few of us will actively consider how we do this and importantly, what we might do to get better at it.

Consider these two little cupcakes. If you had to choose one, which would it be? Would it be the cupcake with the cherry on, or the other one? The bigger or the smaller one? Neither? What do you think you would base your choice on? What are you experiencing when thinking about how you might make a decision?

Consider these two little cupcakes. If you had to choose one, which would it be? Would it be the cupcake with the cherry on, or the other one? The bigger or the smaller one? Neither? What do you think you would base your choice on? What are you experiencing when thinking about how you might make a decision?

I once met a brilliant person whose life was in perpetual chaos. By way of explanation, he said, “I just seem to make bad choices“. Whether we are considering the humble cupcake or some major life or business decisions the fact is that decision making comes down to making choices. The choice may be dressed up as logic or reason, but personal judgment, skill and experience are significant influences on how we decide.

Ultimately our decisions are based on our preferences and our preferences are driven by some pretty complex interactions. If we want to make better choices in life or in business then we need to understand these interactions and exert greater control over them.

Knowing Yourself is the beginning of Wisdom

For over 2,500 years – ever since the days of the great Greek philosophers – we have known our decisions are based upon three main elements referred to by Aristotle as Ethos, Pathos and Logos:

- Whether we consider those presenting us with a decision are to be believed and are trustworthy referred to as ethos

- Whether something feels right or has an emotional appeal, sometimes referred to as pathos

- Whether the decision is logical or reasonable, based on what we know referred to as logos

Many recent advances in neuroscience support these notions.

Fundamentally our decision making involves a complex interplay between the stuff of our emotional selves – which is intuitive, metaphorical, automatic, impressionistic – and our reason – the rational, analytical, rule-based part of us often referred to as the human mind. And thrown into the mix are some regulating factors relating to our ethics, beliefs and values – the things of ethos.

These rational and emotional systems have evolved to work together and in competition with each other. Our rational system is slow, tires easily and often plays a supporting role to our intuitive system. Whether we like it or not we effectively post-rationalise decisions that we have made at a highly intuitive and emotional level. (A crucial popular reference here is Dr Steve Peter’s Chimp Paradox and the very long understood System 1 and System 2 thinking made popular in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow)

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honours the servant and has forgotten the gift.” Albert Einstein

In business, however, there is a tendency to favour and promote the rational part of ourselves over our intuitive thinking system. The trouble is that reasoned judgments are based on what has happened in the past or on what others have experienced. So just relying on rational thinking is not overly useful when making decisions about the future, especially in complex environments.

What we need to strive for is balance in our decision making, enabling out thinking systems to work together in dialogue.

Here’s some thoughts on how we might do that.

How we reflect on the world matters

Our brains have developed to make the strange familiar and what we see is often what we look for. We quickly categorise thoughts and ideas, in order to make sense of the world. So we have a tendency to make speedy judgments and accept the first solution to a problem.

In an increasingly complex and uncertain world we need to process a lot of information quickly, see multiple possibilities (rather than leap to the first solution), and respond flexibly to the changing environment.

Insights from the ancient Greeks and Persians are that critical observation of the world is fundamental to man developing different ways of seeing and making great decisions. Insights from neuroscience teach us that the act of reflection is incredibly valuable in increasing the positive impact of decisions, helping us make more accurate decisions, more consistently.

And herein lies a challenge. In fast-paced environments we tend to spend less time reflecting and more time doing, simply moving from one task to another in order to keep pace with change.

What we actually need to strive for is more constructive, active and frequent reflection that focuses on both reflexive and recursive thinking.

- Reflexive thinking – a focus on understanding the cause and effect of a decision or course of action

- Recursive thinking – understanding repeating patterns and cycles

The most successful leaders act beyond convention through reflexive and recursive knowing – through trial, error and learning from both cause and effect and the repeating patterns that occur within organisations and individual’s lives.

To do this we need to develop habits of observing situations from multiple perspectives, continually reflecting on the context in which we find ourselves and look for the patterns in our environment.

All of which means we need to pause for longer and more often.

Increasing perspectives through dialogue in decision-making

In thinking about an approach to decision making we can again look to the Greek philosophers. Consider the great tradition of dialectics. Dialectics is about setting out a constructive dialogue. At the heart of an approach is the idea that the best decisions are made through keeping dialogue going and that the best decision-makers will have a broad view across all the influences in a system.

So if we can balance the stuff of rational thought with that of our emotions and intuitions and take account of our ethics and beliefs, allowing our minds to engage in dialogue within these different zones can we not increase the accuracy with which we make decisions?

Ironically, humanity happens to manage this process very well and without much training! The challenge is that education systems, business processes and expectations that favour reason above all else have led to other aspects involved in good normal decision-making to be squeezed out or minimised.

A decision making architecture

So here is a proposed decision-making architecture that we can apply to life or business decisions.

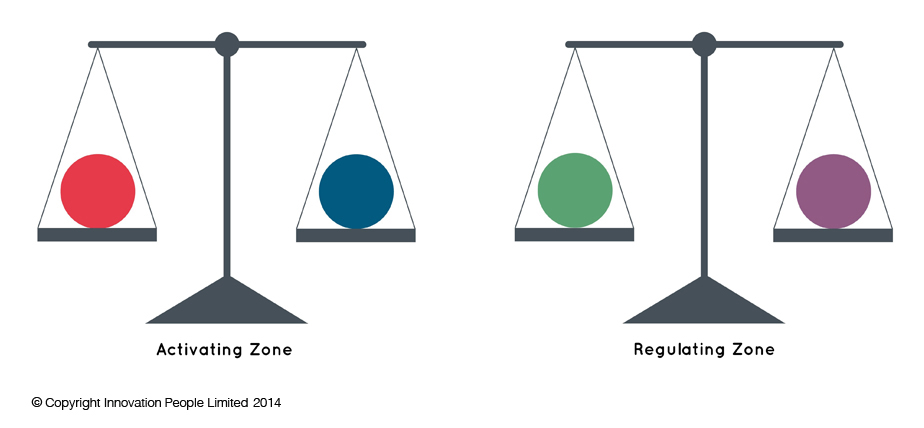

We know people prefer to make binary choices between alternatives. However we are often faced with “noisy” signals from our environment and distortion in our decision-making pathways which reduces the accuracy of decision making in complex environments. If we can create dialogue between a series of paired thinking options across thinking zones we can allow our minds to more easily make decisions. This involves a dialogue between what I refer to as the Activating Zone and the Regulating Zone. The Activating Zone is made up of two parts. Here we access our intuition and imagination (the blue zone) and balance this with knowledge and reason (the red zone). In this sense we listen to our intuition – those flashes of insight and gut responses – and then test and qualify these against what we know and what we can reason.

This involves a dialogue between what I refer to as the Activating Zone and the Regulating Zone. The Activating Zone is made up of two parts. Here we access our intuition and imagination (the blue zone) and balance this with knowledge and reason (the red zone). In this sense we listen to our intuition – those flashes of insight and gut responses – and then test and qualify these against what we know and what we can reason.

The Regulating Zone also consists of a pair of elements. We take account of our ethics and beliefs (the green zone influenced by the context in which we make decisions), and behaviours and values (the purple zone which is all about how we respond as individuals).

Better decisions

The more we are able to create dialogue between these zones the more we will be able to spot patterns and the influences of cause and effect, enabling greater clarity in decision making.

I have utilised this framework with CEO’s and other decision makers within private and public sector organisations through to working with young people from challenging multi-cultural, multi-faith communities over the past two years. In practice users have found this simple decision-making architecture to be a highly practical tool which increases the accuracy of their decisions and the speed with which they make them.

I believe this approach can actively increase the accuracy with which we develop strategies, action plans and predict future outcomes (known as Heuristics) and help people to make the best possible choices through weighing a pattern of associations.

Michael Croft – Guest Contributor